Q&a Review for Pance and Panre Powered by Prepu

| Q | |

|---|---|

| Q q | |

| (Meet below) | |

| |

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Latin script |

| Type | Alphabetic and Logographic |

| Language of origin | Greek language Latin language |

| Phonetic usage | (Table) |

| Unicode codepoint | U+0051, U+0071 |

| Alphabetical position | 17 |

| History | |

| Evolution |

|

| Fourth dimension menses | Unknown to present |

| Descendants | • Ƣ • Ɋ • ℺ • Ԛ |

| Sisters | Φ φ Ф ק ق ܩ ࠒ 𐎖 ቀ Փ փ Ֆ ֆ |

| Variations | (See below) |

| Other | |

| Other messages ordinarily used with | q(x) |

Q, or q, is the seventeenth letter of the mod English alphabet and the ISO bones Latin alphabet. Its name in English is pronounced , most commonly spelled cue, but also kew, kue and que.[1]

History

| Egyptian hieroglyph wj | Phoenician qoph | Greek Qoppa | Etruscan Q | Latin Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| | | | | |

The Semitic audio value of Qôp was /q/ (voiceless uvular stop), and the form of the letter of the alphabet could accept been based on the heart of a needle, a knot, or even a monkey with its tail hanging downwards.[two] [three] [4] /q/ is a sound common to Semitic languages, just not found in many European languages.[a] Some take even suggested that the class of the letter Q is fifty-fifty more than ancient: it could have originated from Egyptian hieroglyphics.[v] [6]

In Greek, qoppa (Ϙ) probably came to represent several labialized velar stops, amongst them /kʷ/ and /kʷʰ/.[7] As a result of later on sound shifts, these sounds in Greek changed to /p/ and /pʰ/ respectively.[8] Therefore, qoppa was transformed into two messages: qoppa, which stood for the number 90,[nine] and phi (Φ), which stood for the aspirated audio /pʰ/ that came to be pronounced /f/ in Modern Greek.[10] [xi]

The Etruscans used Q in conjunction with V to represent /kʷ/, and this usage was copied by the Romans with the rest of their alphabet.[four] In the primeval Latin inscriptions, the letters C, 1000 and Q were all used to represent the two sounds /1000/ and /ɡ/, which were not differentiated in writing. Of these, Q was used earlier a rounded vowel (e.m. ⟨EQO⟩ 'ego'), K before /a/ (e.1000. ⟨KALENDIS⟩ 'calendis'), and C elsewhere.[12] Later, the use of C (and its variant G) replaced most usages of One thousand and Q: Q survived only to represent /g/ when immediately followed by a /w/ sound.[13]

Typography

The 5 most mutual typographic presentations of the capital letter Q.

A long-tailed Q as drawn past French typographer Geoffroy Tory in his 1529 book Champfleury

A brusk trilingual text showing the proper use of the long- and short-tailed Q. The brusk-tailed Q is only used when the word is shorter than the tail; the long-tailed Q is even used in all-capitals text.[14] : 77

Uppercase "Q"

Depending on the typeface used to typeset the alphabetic character Q, the letter'due south tail may either bisect its bowl as in Helvetica,[15] see the bowl as in Univers, or lie completely outside the bowl equally in PT Sans. In writing block messages, bisecting tails are fastest to write, as they require less precision. All 3 styles are considered as valid, with most serif typefaces having a Q with a tail that meets the circumvolve, while sans-serif typefaces are more than equally split betwixt those with bisecting tails and those without.[16] Typefaces with a disconnected Q tail, while uncommon, take existed since at to the lowest degree 1529.[17] A mutual method among typographers to create the shape of the Q is by simply adding a tail to the letter O.[16] [18] [19]

Sometime-style serif fonts, such as Garamond, may incorporate two capital Qs: one with a brusque tail to be used in brusk words, and another with a long tail to be used in long words.[17] Some early metal type fonts included up to 3 different Qs: a brusk-tailed Q, a long-tailed Q, and a long-tailed Q-u ligature.[14] This print tradition was alive and well until the 19th century, when long-tailed Qs roughshod out of favor: even recreations of classic typefaces such as Caslon began being distributed with only curt Q tails.[20] [14] Not a fan of long-tailed Qs, American typographer D. B. Updike celebrated their demise in his 1922 book Press Types, claiming that Renaissance printers made their Q tails longer and longer simply to "outdo each other".[fourteen] Latin-language words, which are much more probable than English words to comprise "Q" as their first alphabetic character, have also been cited as the reason for their existence.[14] The long-tailed Q had fallen completely out of use with the appearance of early digital typography, equally many early digital fonts could not cull dissimilar glyphs based on the give-and-take that the glyph was in, just it has seen something of a improvement with the advent of OpenType fonts and LaTeX, both of which can automatically typeset the long-tailed Q when it is called for and the curt-tailed Q when not.[21] [22]

Owing to the allowable variation in the Q, the letter of the alphabet is a very distinctive characteristic of a typeface;[16] [23] similar the ampersand, the Q is cited as a alphabetic character that gives typographers a run a risk to express themselves.[4]

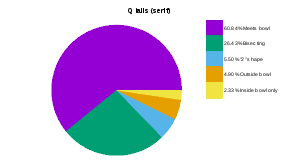

Identifont, an automated typeface identification service that identifies typefaces past questions about their appearance, asks about the Q tail second if the "sans-serif" option is chosen.[24] Out of Identifont's database, Q tails are divided thus:[25]

Some typographers prefer one "Q" design over another: Adrian Frutiger, famous for the aerodrome typeface that bears his name, remarked that virtually of his typefaces feature a Q tail that meets the bowl and and so extends horizontally.[xix] Frutiger considered such Qs to make for more than "harmonious" and "gentle" typefaces.[19] Some typographers, such equally Sophie Elinor Brown, take listed "Q" as beingness among their favorite letters.[26] [27]

Lowercase "q"

A comparison of the glyphs of ⟨q⟩ and ⟨g⟩

The lowercase "q" is normally seen as a lowercase "o" or "c" with a descender (i.e., downward vertical tail) extending from the correct side of the bowl, with or without a swash (i.e., flourish), or even a reversed lowercase p. The "q"'s descender is usually typed without a swash due to the major fashion difference typically seen between the descenders of the "g" (a loop) and "q" (vertical). When handwritten, or every bit role of a handwriting font, the descender of the "q" sometimes finishes with a rightward swash to distinguish it from the letter "g" (or, peculiarly in mathematics, the digit "9").

Pronunciation and use

| Most common pronunciation: /q/ Languages in italics do not use the Latin alphabet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linguistic communication | Dialect(s) | Pronunciation (IPA) | Environment | Notes |

| Albanian | /cç/ | |||

| Azerbaijani cluster | /ɡ/ | |||

| Dogrib | /ɣ/ | Official orthography | ||

| English | /thou/ | Mainly used in ⟨qu⟩ /kw/ | ||

| Fijian | /ᵑɡ/ | |||

| French | /k/ | By and large used in ⟨qu⟩ /k/ | ||

| Galician | /k/ | Only used in ⟨qu⟩ /g/ | ||

| German | Standard | /k/ | Just used in ⟨qu⟩ /kv/ | |

| Hadza | /!/ | |||

| Indonesian | /k/ | Only used in loanwords for religion and science | ||

| Italian | /one thousand/ | But used in ⟨qu⟩ /kw/ | ||

| Ket | /q/~/qχ/ | |||

| /ɢ/ | After /ŋ/ | |||

| K'iche | /qʰ/ | |||

| Kiowa | /kʼ/ | |||

| Kurdish | /q/ | |||

| Maltese | /ʔ/ | |||

| Standard mandarin | /t͡ɕʰ/ | |||

| Menominee | /ʔ/ | |||

| Mi'kmaq | /x/ | |||

| Mohegan-Pequot | /kʷ/ | |||

| Nuxalk | /qʰ/ | |||

| Portuguese | /thou/ | But used in ⟨qu⟩ /1000/ | ||

| Somali | /q/~/ɢ/ | |||

| Sotho | /!kʼ/ | |||

| Spanish | /chiliad/ | Only used in ⟨qu⟩ /thou/ | ||

| Swedish | /k/ | Primitive, uncommon spelling | ||

| Vietnamese | Northern, Primal | /k/ | But used in ⟨qu⟩ /kw/ | |

| Southern | silent | Simply used in ⟨qu⟩ /w/ | ||

| Võro | /ʔ/ | |||

| Wolof | /qː/ | |||

| Xhosa | /!/ | |||

| Zulu | /!/ | |||

Phonetic and phonemic transcription

The International Phonetic Alphabet uses ⟨q⟩ for the voiceless uvular stop.

English standard orthography

In English language, the digraph ⟨qu⟩ most oftentimes denotes the cluster ; however, in borrowings from French, it represents , as in 'plaque'. See the list of English words containing Q non followed past U. Q is the second least frequently used letter in the English language language (subsequently Z), with a frequency of just 0.1% in words. Q has the fourth fewest English words where information technology is the get-go letter, later on X, Z, and Y.

Other orthographies

In most European languages written in the Latin script, such every bit in Romance and Germanic languages, ⟨q⟩ appears most exclusively in the digraph ⟨qu⟩. In French, Occitan, Catalan and Portuguese, ⟨qu⟩ represents /k/ or /kw/; in Castilian, it represents /thou/. ⟨qu⟩ replaces ⟨c⟩ for /k/ before forepart vowels ⟨i⟩ and ⟨e⟩, since in those languages ⟨c⟩ represents a fricative or affricate before front vowels. In Italian ⟨qu⟩ represents [kw] (where [west] is the semivowel allophone of /u/). In Albanian, Q represents /c/ as in Shqip.

It is not considered to be part of the Cornish (Standard Written Class), Estonian, Icelandic, Irish, Latvian, Lithuanian, Shine, Serbo-Croatian, Scottish Gaelic, Slovenian, Turkish, or Welsh alphabets.

⟨q⟩ has a wide variety of other pronunciations in some European languages and in non-European languages that have adopted the Latin alphabet.

Other uses

The majuscule Q is used as the currency sign for the Guatemalan quetzal.

The Roman numeral Q is sometimes used to represent the number 500,000.[28]

In Turkey the use of the alphabetic character Q was banned between 1928 and 2013. This constituted a problem for the Kurdish population in Turkey as the alphabetic character was a office of the Kurdish alphabet. The ones who used the letter of the alphabet Q, were able to be prosecuted and sentenced to prison terms ranging from half dozen months to ii years.[29]

- Q with diacritics: ʠ Ɋ ɋ q̃

- Small-scale upper-case letter q: ꞯ (Used in Japanese linguistics[xxx])

- Gha: Ƣ ƣ

Ancestors and siblings in other alphabets

- 𐤒 : Semitic letter Qoph, from which the following symbols originally derive

- Ϙ ϙ: Greek letter Koppa

- 𐌒 : One-time Italic Q, which is the ancestor of mod Latin Q

- Ԛ ԛ : Cyrillic letter Qa

- Ϙ ϙ: Greek letter Koppa

Derived signs, symbols and abbreviations

- ℺ : rotated capital Q, a signature mark

- Ꝗ ꝗ, Ꝙ ꝙ : Various forms of Q were used for medieval scribal abbreviations[31]

Computing codes

| Preview | Q | q | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER Q | LATIN Pocket-size LETTER Q | ||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | december | hex |

| Unicode | 81 | U+0051 | 113 | U+0071 |

| UTF-8 | 81 | 51 | 113 | 71 |

| Numeric grapheme reference | Q | Q | q | q |

| EBCDIC family | 216 | D8 | 152 | 98 |

| ASCII 1 | 81 | 51 | 113 | 71 |

- 1 As well for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings.

Other representations

See besides

- List of English words containing Q not followed by U

- Listen your Ps and Qs – English-language idiom

- Q gene – Parameter describing the longevity of energy in a resonator relative to its resonant frequency

- Q# – Programming lang. for quantum algorithms

- Generalized coordinates – System configuration relative to another

References

- ^ "Q", Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989).

Merriam-Webster's Tertiary New International Dictionary of the English language Linguistic communication, Entire (1993) lists "cue" and "kue" every bit current. James Joyce used "kew"; it and "que" remain in use. - ^ Travers Wood, Henry Craven Ord Lanchester, A Hebrew Grammar, 1913, p. 7. A. B. Davidson, Hebrew Primer and Grammar, 2000, p. 4 Archived 2017-02-04 at the Wayback Automobile. The meaning is doubtful. "Eye of a needle" has been suggested, and also "knot" Harvard Studies in Classical Philology vol. 45.

- ^ Isaac Taylor, History of the Alphabet: Semitic Alphabets, Part 1, 2003: "The old caption, which has again been revived by Halévy, is that it denotes an 'ape,' the character Q existence taken to stand for an ape with its tail hanging down. Information technology may also be referred to a Talmudic root which would signify an 'aperture' of some kind, as the 'centre of a needle,' ... Lenormant adopts the more usual explanation that the discussion means a 'knot'.

- ^ a b c Haley, Allan. "The Letter Q". Fonts.com. Monotype Imaging Corporation. Archived from the original on 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2017-02-03 .

- ^ Samuel, Stehman Haldeman (1851). Elements of Latin Pronunciation: For the Apply of Students in Language, Law, Medicine, Zoology, Botany, and the Sciences By and large in which Latin Words are Used. J.B. Lippincott. p. 56. Archived from the original on 2021-08-xvi. Retrieved 2020-11-nineteen .

- ^ Hamilton, Gordon James (2006). The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts. Cosmic Biblical Association of America. ISBN9780915170401. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2020-09-sixteen .

- ^ Woodard, Roger G. (2014-03-24). The Textualization of the Greek Alphabet. p. 303. ISBN9781107729308. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2020-11-19 .

- ^ Noyer, Rolf. "Principal Sound Changes from PIE to Greek" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Department of Linguistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-04. Retrieved 2017-02-03 .

- ^ Boeree, C. George. "The Origin of the Alphabet". Shippensburg Academy. Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 2016-12-04. Retrieved 2017-02-03 .

- ^ Arvaniti, Amalia (1999). "Standard Mod Greek" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 2 (29): 167–172. doi:10.1017/S0025100300006538. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Miller, D. Gary (1994-09-06). Ancient Scripts and Phonological Noesis. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 54–56. ISBN9789027276711. Archived from the original on 2021-08-eighteen. Retrieved 2020-11-19 .

- ^ Bispham, Edward (2010-03-01). Edinburgh Companion to Ancient Hellenic republic and Rome. Edinburgh Academy Press. p. 482. ISBN9780748627141. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2020-11-19 .

- ^ Sihler, Andrew 50. (1995), New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin (illustrated ed.), New York: Oxford University Printing, p. 21, ISBN0-19-508345-eight, archived from the original on 2016-11-09, retrieved 2015-12-24

- ^ a b c d e Updike, Daniel Berkeley (1922). Press types, their history, forms, and use; a study in survivals. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN1584560568 – via Cyberspace Annal.

- ^ Ambrose, Gavin; Harris, Paul (2011-08-31). The Fundamentals of Typography: Second Edition. A & C Black. p. 24. ISBN9782940411764. Archived from the original on 2021-08-19. Retrieved 2020-11-19 .

...the bisecting tail of the Helvetica 'Q'.

- ^ a b c Willen, Bruce; Strals, Nolen (2009-09-23). Lettering & Type: Creating Letters and Designing Typefaces. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 110. ISBN9781568987651. Archived from the original on 2021-08-15. Retrieved 2020-11-19 .

The bowl of the Q is typically similar to the bowl of the O, although non always identical. The style and blueprint of the Q's tail is often a distinctive feature of a typeface.

- ^ a b Vervliet, Hendrik D. L. (2008-01-01). The Palaeotypography of the French Renaissance: Selected Papers on Sixteenth-century Typefaces. BRILL. pp. 58 (a) 54 (b). ISBN978-9004169821. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2020-11-19 .

- ^ Rabinowitz, Tova (2015-01-01). Exploring Typography. Cengage Learning. p. 264. ISBN9781305464810. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2020-11-19 .

- ^ a b c Osterer, Heidrun; Stamm, Philipp (2014-05-08). Adrian Frutiger – Typefaces: The Complete Works. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 97 (a) 183 (b) 219 (c). ISBN9783038212607. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2020-11-19 .

- ^ Loxley, Simon (2006-03-31). Blazon: The Secret History of Letters. I.B.Tauris. ISBN9780857730176. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2020-xi-19 .

The uppercase roman Q...has a very long tail, but this has been modified and reduced on versions produced in the following centuries.

- ^ Fischer, Ulrike (2014-11-02). "How to force a long-tailed Q in EB Garamond". TeX Stack Exchange. Archived from the original on 2017-02-04. Retrieved 2017-02-03 .

- ^ "What are "Stylistic Sets?"". Typography.com. Hoefler & Co. Archived from the original on 2017-02-04. Retrieved 2017-02-03 .

- ^ Bosler, Denise (2012-05-xvi). Mastering Type: The Essential Guide to Typography for Print and Web Design. F+Due west Media, Inc. p. 31. ISBN978-1440313714.

Messages that comprise truly individual parts [are] S, ... Q...

- ^ "two: Q Shape". Identifont. Archived from the original on 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2017-02-01 .

- ^ "3: $ style". Identifont. Archived from the original on 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2017-02-02 . To get the numbers in the table, click Question 1 (serif or sans-serif?) or Question 2 (Q shape) and change the value. They announced under X possible fonts.

- ^ Heller, Stephen (2016-01-07). "We asked 15 typographers to describe their favorite letterforms. Hither's what they told us". WIRED. Archived from the original on 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2017-02-03 .

- ^ Phillips, Nicole Arnett (2016-01-27). "Wired asked 15 Typographers to introduce us to their favorite glyphs". Typograph.Her. Archived from the original on 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2017-02-03 .

- ^ Gordon, Arthur Due east. (1983). Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy . University of California Printing. pp. 44. ISBN9780520038981 . Retrieved three October 2015.

roman numerals.

- ^ "Ban on Kurdish messages to exist lifted with democracy package - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 2022-01-17. Retrieved 2022-01-17 .

- ^ Barmeier, Severin (2015-10-10), L2/15-241: Proposal to encode Latin modest majuscule Q (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-14, retrieved 2018-06-19

- ^ Everson, Michael; Baker, Peter; Emiliano, António; Grammel, Florian; Haugen, Odd Einar; Luft, Diana; Pedro, Susana; Schumacher, Gerd; Stötzner, Andreas (2006-01-30). "L2/06-027: Proposal to add Medievalist characters to the UCS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-19. Retrieved 2018-03-24 .

Notes

- ^ See references at Voiceless uvular stop#Occurrence

External links

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Q